Monday, May 28, 2012

Inside and outside 'Wit's End'

Werner Herzog

The 'Wit's End' Story

One of the first images in Wit's End AKA The GI Executioner is of an elderly Chinese man lying on his side preparing then smoking an opium pipe. Unfortunately this gentleman isn't a character we're going to learn anything about, he appears once more, at the end of the titles (about 70 seconds later) continuing his pursuit of opiated bliss (presumably for real) over the celebratory statement 'Film shot entirely on location in Singapore'. Aside from some interiors in the now long-gone Cathay Keris studio, this claim is true. Filmed in Singapore at the very end of 1969, Wit's End was the first American film to be entirely made in the Lion City until Saint Jack almost a decade later. The reason you almost certainly haven't heard of it is because it fell off the radar until the early 1980s. Exploitation film company Troma, who gleefully acquired cheap movies with some degree of violence, sex and grotesquerie, repackaged Wit's End as The GI Executioner (a title with no relevance to anything in the picture) and it apparently sold well on VHS (and is still available on DVD).

Back in 1969, this is the torrid tale of Dave Dearborn, a washed-up American journalist ex-Marine and would-be novelist-playwright running a groovy nightclub on a boat called The Junk; moored a brief bumboat ride away from Clifford Pier. After the aforementioned opening credits sequence (see above), we first get to meet Dave as he's being joylessly fellated by a local working girl (a real prostitute, according to the film's director). Dave, played by stage actor Tom Keena, is caustically depressed and seems to be at the titular 'wit's end' ("look what I ended up with, a lot of bad memories and this lousy bar"). Pretty quickly he becomes a pawn in a scenario involving the CIA, a local gangster, Chinese and Russian spies. He also has a complicated love life, moving from his local “maiden” to an adoring young American innocent abroad (Janet Wood), a buxom American stripper improbably working a bar in Bugis (Angelique Pettyjohn) and the Big Love of his Life, Mai Lee (Vicky Racimo), mistress of a local gangster, much to Dave's chagrin.

Tonally the film slips all over the place, from bleak, downbeat thriller to softcore farce and exotic espionage caper. Two or three set-pieces oscillate between high camp absurdity and sublimely lurid unpleasantness. Notably the protracted death of Angelique's character on the boat, completely naked and wielding a handgun (prompting the tagline "The Wildest Nude Shootout in Film History"); and the aftermath of a pretty neatly staged mini-massacre in an abandoned building which prompts Dave and Mai Lee to fuck (rather unhygienically) amongst the corpses.

The acting is uneven to say the least, veering from strained competence (Keena) and enjoyably game (Wood and Angelique), to dead wood (most of the locals, the expats and Racimo) and flagrantly atrocious (the guy who plays a British spy disguised as a hippy with a scouse accent).

Also it's impossible to ignore the relentless interrogation of Dave's sexuality. Mostly this is in relation to his muscle-bound 'Kiwi' friend Peter, whose murder sets much of the plot in motion. Despite the fact he has many female lovers, seemingly everyone Dave meets - the girls, the police, the secret agents, the antagonist and even Dave himself, loudly wonder if he's gay, culminating in a scene of leather-bound humiliation at the hands of a flaming super-criminal and his queer minion. It's a very literal enactment of sexual insecurity.

Unsurprisingly this jarring, schizoid work has a complicated production history which I've pieced together through research and correspondence with the director Joel M. Reed in New York (best known today for the notorious Bloodsucking Freaks), and Keith Lorenz in Hawaii. Lorenz is co-credited for devising the story along with fellow Singapore-based journo Ian Ward.

The idea to make a feature film in Singapore comes from Marvin Farkas, a Yank who'd got a taste of the Orient as a sailor in WW2, and returned in the 1950s primarily as a commercial photographer and news cameraman, based out of Hong Kong. As recalled in his memoir An Eastern Saga, Farkas had visited Singapore earlier in the 60s and been smitten. "Marvin said that Singapore was an old fashioned place with seedy cafes and opium dens," Reed says, "(he) had a studio in Hong Kong and raised the money from some old Asian hands." For the story and the script he turned to two young foreign correspondents, Ward and Lorenz, both living in Singapore and, in their spare time, running The Junk, a hip night-club-bar-restaurant on a restored junk-boat. "I had wanted to make a 1969 version of Casablanca," says Lorenz, who wrote a treatment which revisioned Bogart's Rick character as "a disillusioned American foreign correspondent escaping from his war reporting job in Saigon, and drinking and womanizing from a hammock on his junk in the Singapore harbor."

Although the archetype of the White Man Adrift in Asia was hardly original, there are faint pre-echoes here of Paul Theroux’s Singapore novel Saint Jack - a failed American writer adrift in Singapore who gets mixed up with gangsters and spies, and The Junk, while certainly not a brothel, with its “Malay carvings and bevy of attractive girls” (according to The Asia Magazine in ’68) might be some sort of floating precursor to Dunroamin’ – the idyllic club Jack Flowers sets up in Theroux’s book.

Lorenz first came to Singapore in ‘62 as a young advertising man then shifted to Bangkok ("much more wild"), before returning in ‘67 as a foreign correspondent for American media outlets. As Lorenz describes it, the late '60s were a happening period in Southeast Asia: "the Vietnam war was playing out, Sukarno was haywire in Indonesia, massacres in Java, remnants of communist insurgency in Malaysia, the residue of British influence (in Singapore), the rise of Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP, the flavor of a languid, low-rise, Asian port city with still a colonial melange... It was very special." And it was definitely worth trying to capture some of those flavours in a movie.

Farkas would shoot the thing, but he brought out a young painter from New York (famous for illustrating classic Jazz album covers) called David Young to direct. According to Lorenz, Young "came out to Singapore early for script writing, location scouting, hiring, and pre-production with my help," but he was troubled and drinking too much. He'd "just begun to get the ambience of Singapore when he sort of fell apart." Joel M. Reed enters the scenario at this point. The fledgling director had bumped into Farkas previously in New York and was recruited to track down Young, who'd returned to the city with Farkas's cash and a promise to write a producible script. Farkas joined them and Reed witnessed an almighty row between the two of them, Young demanding more money. "At one point in the conversation Marvin said, 'That does it. Joel's directing the picture.' I stupidly accepted and ruined a good part of my career." Although he’d started film-making for legendary skinflick producer Joe Sarno ("by accident" he says), Reed hoped he was heading to Broadway and/or Hollywood.

He read the first draft and saw that Young had "copied a script of Casablanca, changed the names, and moved the location to Singapore." Lorenz, who still has a copy of this draft, says it was faithful to his and Ward's original story. Reed began a rewrite, keeping the Dave Dearborn character and some of his dialogue and love life, while adding the spy plot and the more explicit sexual and violent elements to “perk up a rather dull script”. Although Lorenz and Ward’s place, The Junk would remain a key location, Lorenz wasn't happy about the changes. "He (Reed) persuaded the cash people to let him make it raunchy and campy, whatever you want to call it. He decided to be both writer as well as director, and got his way… I lost all interest quite soon... (and) it could have been great." Reed feels he did the best he could with the material, but "when I saw Singapore for the first time, I knew the whole script was wrong. The expats that backed the movie still envisioned it as a 1940s movie. Even Saint Jack didn't get it right."

Incredibly, given the censorship problems that Peter Bogdanovich envisaged when he was shooting Saint Jack a decade later, Wit's End was seemingly accepted by the authorities."It was an official production," Reed recalls,"The Government read the script and I met Lee Kwan Yew… (at) some sort of official reception… They had no trouble with the script since it was apolitical." Reed claims that officials demanded to be present only when nude scenes were shot and "I think our casting director got one laid in a dressing room."

The production coincided with an event that looms large in the secret history of Singapore's film industry - in 1969, Oscar-winning director Fred Zinnemann intended to shoot his adaptation of Andre Malraux's Man's Fate in Singapore. When Wit's End arrived to crew up, Reed says, "Everybody stuck their noses up at us…they all were going to be in major picture. We were peanuts." Then MGM abruptly pulled the plug on Man’s Fate (which was never made), "and the same people were soon chasing me down the street and banging on my hotel door."

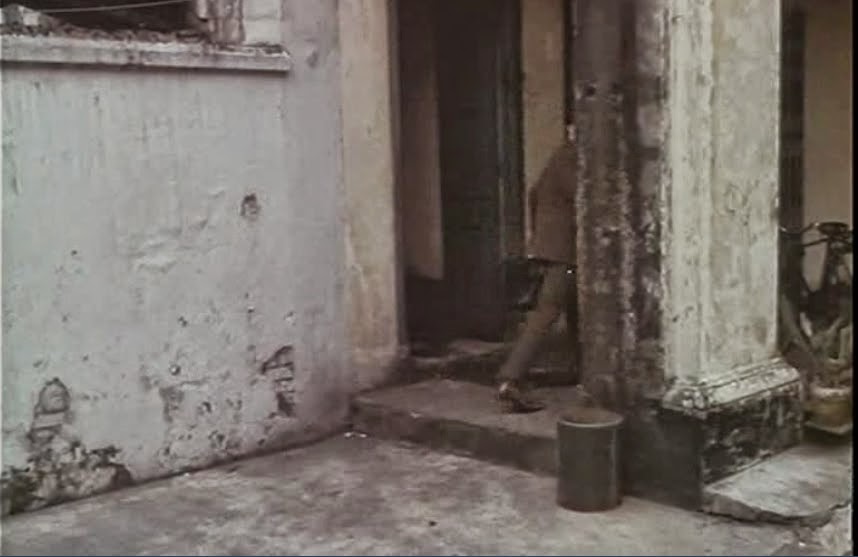

Aside from the aforementioned Clifford Pier and The Junk, they shot in Chinatown, Bugis Street, rural Pasir Ris and Mount Faber, Reid Bridge and Boat Quay, Raffles Hotel (a scene in the temporary lobby), the Ocean Park Hotel (unconvincingly standing in for Raffles upstairs), a swanky mansion on Garlick Avenue as the gangster’s lair, and an abandoned, graffiti-strewn building in the Tiger Balm Estate. There are two lengthy scenes displaying young Singaporeans, expats and ‘girls’ wildly grooving to music - snapshots of how late-sixties hedonism looked in Singapore - one supposedly in a Bugis Street bar called Adonis, and another apparently shot on The Junk (which leads to a dreadful bit of continuity when Dave leaves the party at The Junk and then gets on a boat to… The Junk). There are also several scenes in depopulated back alleys, and many of the locations have a ‘dead’ atmosphere, as if the city has been emptied of all but a few self-conscious extras, although occasionally a child or an old man can be seen half-hiding within a frame.

Long passages of the film are sluggish, and after looking at the sequences closely, you notice how scenes have been elongated. Much of the time characters enter and exit rooms, kickstarting scenes that could begin much later and resolving scenes that have long outstayed their welcome. Often, even the briefest of scenes begins and ends on an ‘empty’ frame. This may be less a stylistic device and more a way of ‘padding’ out meagre footage. But unknowingly this becomes a gift to those of us looking from a different perspective, the fascinated watchers from the future, who see every second of Wit's End as a rare and precious document of what Singapore was during Christmas 1969, a world that’s almost entirely disappeared, but shimmers back to life for a moment, thanks to this largely thankless film.

Back then The Straits Times blessed (or cursed) the production with some breathlessly enthusiastic coverage, including an interview with Tom Keena who declared straight-faced that he was so immersed in the role that “I am Dearborn now.” Six months later, a writer for (long defunct) local entertainment magazine Fanfare travelled to Hong Kong to ask one of the producers, Michel Renard, what was going on. Renard’s confident that it will “go well in the States” (“… and I hear our color’s supposed to be good too.”) and that Singapore won’t get to see itself “mirrored on the celluloid screen” (the reporters phrase) until early 1971.

Actually, Singapore never got to see Wit’s End, and still hasn’t to this day. The film had a Stateside release in 1973 under the title Dragon Lady (“packs the punch of the Orient!”) but more or less disappeared. Then Farkas’s brother sold it to Troma in the 80s and it was revived and reissued as The GI Executioner with a tagline designed to suggest Death Wish in the Far East, “They tried to kill him ... drug him, torture and pervert him, but they could not stop the one-man execution squad...”

For his part, Reed, who promises more stories about the film in his autobiography, "had a wonderful time and saw a little of the old Singapore and made many friends." The place made enough of an impression for him to write "a light hearted mystery play taking place in an old Mansion on East Coast Road which manages to combine both the old and new."

Lorenz didn't see it until the '90s, when Reed sent him a tape, and although he disliked the film, "It was nostalgic seeing the Junk and the old Singapore that I knew. Some of Dearborn's lines conveyed what I had intended: a disgruntled, disillusioned war correspondent who had enough of the horror of war, and just wanted to hang loose on a boat."

Huge thanks to Joel M. Reed and Keith Lorenz.