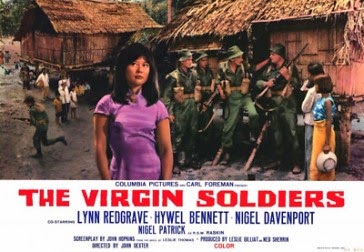

The Virgin Soldiers, John Dexter, shot: 1967/released: 1969

“It rained a lot, and steamed when the sun shone. It was always hot. But it was safe.”

A few weeks ago Leslie Thomas died. He was a relatively prolific novelist producing a book a year for a long time, but, as the obits made clear, best known as the author of The Virgin Soldiers, a fictionalised account of his years as a conscripted private stationed in Malaya, and more specifically, Singapore between 1949 and ’51. This was the early phase of the ‘Malayan Emergency’ when British forces fought viciously with anti-colonial, pro-communist guerilla squads who’d shifted from being a local resistance against the invading Japanese (trained and armed by the Allies) to terrorists determined to ‘free’ Malaya from the British. It's a conflict little represented in fiction before or since. The literary precursors to Thomas’s book were Anthony Burgess’s Malayan Trilogy in the late 50s, and Michael Keon’s The Durian Tree in ‘59, filmed in 1964 as The Seventh Dawn, a forgotten attempt to render the Emergency as a big-budget war epic. None of these would have the popular impact of The Virgin Soldiers.

Published in 1966, a good fifteen years later after these formative events for Thomas (but only six years after the Emergency was declared over) the book was a massive bestseller in its time, both in the UK and America. An irreverent, iconoclastic look at military life in the aftermath of World War Two, The Virgin Soldiers ("the best three words I ever wrote" Thomas later said) was firmly anti-war, anti-authoritarian and, most importantly, pro-sex, chiming perfectly with the period. Sales were aided by a series of lurid book covers (the first edition projects an image of a soldier in a jungle, Maurice Binder-style, onto a naked female torso) and its reputation for being “intensely erotic”, as Publisher’s Weekly helpfully blurbed for the paperback.

The story’s recounted mostly from the point-of-view of Thomas’s alter-ego, Brigg (ironically General Briggs was responsible for British strategy during the Emergency), a vaguely working class chap in his early 20s whose National Service stint brings him to Panglin Camp (a jokily renamed Tanglin Barracks, although Thomas was actually stationed at Nee Soon Camp) to be a pay clerk, doing admin in the arse-end of beyond (miles from the action), where the most useless, stupid and unfit for duty are deliberately “mislaid by the army".

It’s about the tedium of the posting - the practical jokes, the petty squabbles, being horny and bored and powerless in a foreign country. But riots break out in Singapore and even the pen-pushers get into the fray. At first Brigg’s only interested in losing his virginity; sights are set on Philippa, the daughter of the Sergeant Major, but he settles for ‘Juicy’ Lucy, a pretty Chinese dancer at the Liberty Club downtown, who’s never had a virgin before and loves it (coining the titular phrase). Meanwhile Philippa, resentful of her Singapore life, whose father openly worries she’s a lesbian, is deflowered by Driscoll, the tough-bastard Sergeant haunted by a wartime incident in which he accidentally shot his own lads, and whose hatred of the other Sergeant Wellbeloved, a cruel, incompetent racist constantly boasting of military heroics, becomes a crucial narrative thread.

Thomas sketches miniatures of Brigg’s mates - the train-obsessive Sinclair, openly gay Villiers and Foster, bespectacled Brook, overweight Fred Organ, and scheming Fenwick (who's convinced he’ll be discharged if he keeps his ears under water until he’s deaf) through a series of episodes big and small. There’s the interminable camp dance, a brutal dog-shooting competition, the anti-British riot (which sees Brigg try to play hero by ‘rescuing’ Philippa and her dotty mother), a long messy fight between Driscoll and Wellbeloved, R&R in Georgetown (where Brigg and Philippa finally have sex) building up to the novel’s climax – Brigg and the boys seeing real action when their train back to Singapore (through the Malayan jungle) is ambushed by bandits.

Thomas sketches miniatures of Brigg’s mates - the train-obsessive Sinclair, openly gay Villiers and Foster, bespectacled Brook, overweight Fred Organ, and scheming Fenwick (who's convinced he’ll be discharged if he keeps his ears under water until he’s deaf) through a series of episodes big and small. There’s the interminable camp dance, a brutal dog-shooting competition, the anti-British riot (which sees Brigg try to play hero by ‘rescuing’ Philippa and her dotty mother), a long messy fight between Driscoll and Wellbeloved, R&R in Georgetown (where Brigg and Philippa finally have sex) building up to the novel’s climax – Brigg and the boys seeing real action when their train back to Singapore (through the Malayan jungle) is ambushed by bandits.

Thomas takes it leisurely, keeps the banter among the men earthy and often genuinely funny, and ensures the spectre of terrible violence is always close. An early chapter begins with the sentence: “When the Japanese had been in Panglin during the war they had taken some Australians down to the cricket field and murdered them.” He does this again and again, shifting from an amusing or relatively innocuous detail into something to do with death, as casually as you might mention a change in the weather.

Singapore is minimally described, like a scrawled map for a weekend visitor. There’s the “village” near the camp, the centre of town where the boys visit the Liberty Club “just off the Padang”. Lucy’s flat’s on “Sarangoon Road (sic)”. When the riot breaks out they roam the city, passing the Cathay cinema (showing Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets) and Raffles Hotel (for “people with money”) and setting up temporary camp in the “Golden World amusement park”. The only Singaporean character (let’s skip “Fuk Yew” the laundryman whose fingers Brigg accidentally shoots off) is Lucy. Sexually generous and deeply whimsical, she’s a stereotype but so fondly drawn that when Brigg finds out she’s been murdered by a gang of British soldiers who thought she’d passed them VD, it’s devastating. Even more so as Brigg pushes his grief away and wonders “if she did have the disease” (she didn’t). When the book was published, Walter Warwick, reviewer for The Straits Times (an expat with his own post-war memories), found it sensationalised, “The Pay Corps was never like this,” he sniffed.

In the late '60s, Ned Sherrin, on a hot-streak after producing That Was The Week That Was, was offered a job as an executive for Columbia Pictures in London. With theatre and TV contacts up the wazoo, Sherrin was a classy hire. The Vietnam War was still raging in Indochina, and the ‘youth picture’ with counter-cultural overtones was emerging as a commercial genre (Columbia were the studio that picked up – and made a fortune from - Easy Rider in ’69), so the story of young guys making love not war, seemed opportunistically right for the studio. Sherrin, by his own admission not a rock n’ roll guy, simply wanted to make a good film capturing the book’s spirit.

Credits for writing the thing are complicated. The top credit, "screenplay", goes to John Hopkins (the bigger font size in the opening credits says it all), but "adaptation" is credited to John McGrath and “additional dialogue” is by Ian La Frenais. Hopkins and McGrath both started off in television, primarily on police procedural Z Cars, episodes of which Hopkins wrote and McGrath directed. McGrath would become a legendary political theatre-maker in the 70s, but in the late ‘60s he was a jobbing screenwriter, adapting his own anti-war play, The Bofors Gun (1968) as well as Len Deighton’s Billion Dollar Brain (1967) for Ken Russell (the Edinburgh International Film Festival just annouced a tribute to his screenwriting this year; The Virgin Soldiers is absent). Hopkins was a prolific writer of lauded ‘Wednesday Plays’ and other one-off TV dramas, and had done a major rewrite on the troubled script for Thunderball (1965). McGrath probably did the first draft (hence the adaptation credit), which was, for whatever reason, substantially rewritten by Hopkins, and sitcom king La Frenais, a specialist in dry funny dialogue, came in for the polish.

The script retained the novel’s major set-pieces, leaning towards Brigg’s point-of-view, including a first-person voice-over narration glueing the various episodes together. As in any adaptation there are big changes and contractions. Rather than have Brigg and Philippa reunite in Georgetown, the film consumates their lust much earlier beside the pipeline during Brigg’s comical rescue, and once that’s done Philippa’s barely seen again. The most fundamental ommission is Lucy’s death, which I presume was just too disturbing to include. The culminative effect of these tweaks is that once Brigg and Philippa lose their respective virginities (rapidly crosscut together in that stylised late '60s style) both the romantic and sensual aspects of the book slacken off. A neater move is to make Wellbeloved's cowardice something that actually happens on-screen, placing him on the ambushed train (hiding in the toilet) in the film’s climax, rather than have Driscoll confront him about something that he reportedly did in the war.

John Dexter, a theatre-director associated with the great post-war theatre generation led by Laurence Olivier, was picked by Sherrin to make his cinema directing debut with The Virgin Soldiers. Hywel Bennett, a Welsh-born, London-raised and RADA trained young actor (with just a few TV credits at that point) got the plum part of Brigg, and established British star Nigel Davenport played Driscoll (around same time he recorded all of HAL’s dialogue for Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Oddysey, and was Michael Caine’s reluctant wartime partner in Andre De Toth’s excellent, underseen Play Dirty), a rather too-young Jack Shepherd was Wellbeloved, and Lynn Redgrave (who’d just played Noel Coward’s Pretty Polly in the TV version of the Singapore-set story) was cast as Philippa, alongside her real-life mother Rachel Kempson (wife of Michael Redgrave), playing her mum.

That particular bit of casting was of vital importance to Singaporeans, according to The Straits Times, who, when they found out, devoted several articles to the “Royal members of British filmdom” deigning to visit the former colony. When filming had been announced earlier in 1967, Cathay’s managing director Tom Hodge, a tireless cheerleader for foreign productions in Singapore, was convinced the decision was due to the “tremendous success” of the Pretty Polly shoot the year before, “when the fullest possible co-operation was given by the Singapore authorities.” Location filming started with a week and a half in Port Dixon, Malaysia for the beach R&R scene and some jungle exteriors, followed by five weeks in Singapore, where they needed an army camp or barracks to stand in for Panglin.

Built in the late 1930s, Selerang Barracks was part of the British forces coastal defences, but when Singapore fell to the Japanese in 1942, it became a prison, containing the overspill of captured British and Australian soldiers from Changi. It would be the site of a notorious stand-off between Commander General Shimpei Fukuye and every military POW in Singapore when the Japanese General demanded prisoners sign a statement promising to cease all escape attempts, after four had been caught fleeing from Changi. When the officers refused, Fukuye had every single prisoner marched into Selerang, squeezing an estimated 15000 men into a space designed for 800, most of them forced to live pressed together in the parade square with only a tiny amount of water and few toilets. At the same time the four escapees were executed on Changi Beach. After several days when it was clear that more would die in these conditions the officers capitulated. The POWs signed the document, many using nonsense or fictional names, Ned Kelly was a popular one with the Australians. This barracks, still under the command of the British Army two years after independence, was granted to The Virgin Soldiers' shoot, with its resident servicemen as extras.

In the lead-up to the arrival of crew, Tom Hodge let slip that “a local girl” might be needed to play Lucy, although that offer was soon downgraded to being a “stand-in” for the Chinese London-based actress Tsai Chin (Fu Manchu’s daughter in several Harry Alan Towers flicks), whose scenes would be shot in London on a set. After auditions they picked Ng Lee Ngo, a student who “seemed to be harbouring an anxiety” according to The Straits Times reporter on the beat. She was replaced by Denise Chew, an ex-Bunny Girl at the Playboy Club in London, glimpsed in the completed film very briefly (in two fleeting shots which keep her face hidden) chucking Brigg’s trousers into an alleyway. Two years later, the reviewer for The Straits Times would describe her performance as “brilliant”.

Filming in Singapore lasted five weeks, with the Redgraves flying in for the last nine days, before everyone shipped out on the 5th of October 1968, to begin a month of shooting on sets built in Shepperton. Almost all the interiors were built and shot there, including the barracks bar for the garrison dance scene, which features an impossibly brief appearance by a pre-stardom David Bowie, being shoved out from behind the bar. Bowie, who would later come to Singapore for real and make a film about it, cut his hair for the part (a big gesture in 1967), and was rewarded with about one second of screen time.

Before filming had started, Sherrin asked Ray Davies, lead singer and songwriter for The Kinks, to write music for the film (and offered him a part - he wisely declined). Davies came up with a new composition, The Virgin Soldiers March for a full orchestra and brass band, and penned some unironic “noble” lyrics to accompany the theme. These were rejected by Columbia who hired two lyricists Eddie Snyder (who co-wrote Strangers in the Night) and Larry Kusik to write lyrics that they believed (according to Sherrin) were “going to lead the whole of young America marching on Washington”. Sherrin declared them “apalling”, and nixed them too (and rightly so, as proven by a tepid vocal version, The Ballard of the Virgin Soldiers recorded by folk singer Leon Bibb in 1970).

Davies’s music (credited to “Raymond Douglas Davies” ensuring it would be lost to only the most die-hard of Kinks fans), manages to be both plaintive and gloriously celebratory. It plays over the opening credit sequence, a relentless monochrome image/photo-montage of young soldiers, from the Napoleonic War through to World Wars One and Two, before we’re dropped into an initially baffling series of shots of uniformed boys in vivid color - the titular “Virgins” - waiting for the national anthem to be over so they get on with a night of drunken debauchery in The Liberty Club. Then we transition into the first pages of the book, with Brigg on early morning tea duty walking through Selerang/Panglin at first light, palm trees looming in the grey-blue sky as Hywel Bennett’s deathly hush of a voice-over sets the scene.

The film starts strong. It’s beautifully shot (by Ken Higgins a TV cameraman whose other notable credit was Georgy Girl), and has the good habit of dropping us into scenes that have already begun. Coming from theatre, John Dexter’s adept at choreographing sizeable groups of actors in the foreground of medium shots (often with some bit of business happening in the background), before cutting to close-ups of one of his young actors, yelling or looking utterly bewildered. It’s crisp and brisk and entertaining, until the episodic trudge of the narrative begins to weigh the film down around the halfway mark, as does the broad, theatrical delivery of the dialogue by most of the young soldier cast, who aside from Bennett (who we’ll get to in a bit) are nothing to write home about (save for Christopher Timothy and an improbable Wayne Sleep, the rest of the lads are destined for lifetimes in soaps and daytime TV).

Cinematic fireworks are saved for the train ambush at the end, which begins with a beautiful tracking shot from the outside, looking into carriage windows at night (prefiguring Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited), and then when the battle begins, deploying more tracking shots to capture the explosions and violent chaos. This entire set-piece was shot in the UK, with mocked-up train interiors in the studio and the exteriors, complete with a crashed Fifteen Guinea Special steam train (one of the last in existence), shot with rural Essex (on some miraculously sunny days for October) standing in for the Malayan jungle. Dexter would never make another film on this scale, he followed The Virgin Soldiers with two peculiar independents, Pigeons (1970) and I Want What I Want (1972), and then returned to theatre and opera.

The aforementioned tone of the book, the way Thomas slides wry details of camp life alongside devastating revelations, proves unadaptable, although Dexter and co give it the good British try. Thomas could write a line like “Fred Organ, heavyweight kicker of anti-personnel mines, wasn’t listening.” but when you show a fat, loveable slob having his body blown-up during a football match, you have to do just that. Thomas's casual shocks (little literary landmines) become big drama on screen. Some things are toned down, as already mentioned, Lucy survives, and the scene where Wellbeloved confronts a naked “Malay girl” alone in her house during a kampong search is, in the book, clearly an attempted rape, foiled by Brigg and company, whereas in the film it’s sinister but not a precursor to violence (Wellbeloved was looking for “a bit of bare tit”, as Driscoll observes, clarifying that he’s a disgusting creep, but not a rapist).

The idea of the ‘anti-hero’ was a topical one in the late '60s, as conflict and rebellion around the world led to a sustained questioning of what exactly a hero was in so much culture of the era. The film never allows us to consider Brigg as a hero for a second, even when he appears to be rescuing Philippa and her mother, he’s clumsy and terrified (just as in the book), and his primary motivation is erotic rather than heroic. During the train ambush the film actually takes Brigg’s anti-heroism further. Trapped in a foxhole with the far more experienced (in the book, traumatised) “jungle soldier” Waller (played by future Commander of the Night’s Watch, James Cosmo), he accidentally causes Waller’s death by calling for him at the wrong moment, which leads into his cowardly departure from combat, saving himself from death by running away and then inadvertently avoiding court-martial by finding a train full of soldiers to come to the rescue.

Hywel Bennett as Brigg. He’s 27 but looks barely 18, and has a striking, open (Bowie-like) androgynous face (a decade before the booze and the fags and the years turned him into Ricki Tarr, John Le Carre’s fucked-up spy-lover in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy - undoubtedly his best performance – and four years before he sexually cavorted again to a Kinks soundtrack in the execrable Percy), he projects a straightforward innocence in The Virgin Soldiers. The film wants Brigg to go to the Heart of Darkness, to have his innocence wiped away and demonstrates this by flinging dirt on his face before important close-ups, as if that’s enough. One wonders how Bennett would have handled Brigg reacting to Lucy’s murder, but we’ll never know. The film doesn’t want to end the way the book does, with Brigg on the truck out of Singapore and a terrible gag about the Chinese laundryman, so it deliberately fumbles the joke and closes a few seconds later, once Brigg’s revisited all the freeze-framed faces of the film’s dead, with himself at the end of it. And then we see those monochrome images from the titles again, the eternal boy-soldiers of history, destined to be victims of other people’s pride and greed and stupidity forever more, and Ray Davies’ funeral march begins a final time, majestic, sad and bitterly ironic.

Although shooting was finished well before Christmas 1967, the film took an unnaccountably look time to edit and appears to have been kept ‘on the shelf’ until almost two years later, October 1969, when it was released in the UK, and February 1970 for America. Finally showing up in Singapore cinemas in May of that year. It was relatively successful, enough to be referred to repeatedly as a “hit” in all of Thomas’s obituaries, although it didn’t trouble any top ten box office lists. These were during vintage months for cinema, especially in terms of films that pushed the barriers on sexuality and violence. Thinking about The Virgin Soldiers alongside Lindsay Anderson's If... or even Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (released a few months earlier), makes it seem like a pretty minor achievement.

Thomas followed The Virgin Soldiers with a several novels that mixed military characters, humour and sex, before returning to Brigg again with Onward Virgin Soldiers, which jumps forward in time to discover Brigg (improbably) enlisted in the regular army and serving in peaceful Hong Kong in the 1970s. Four years later Thomas completed the trilogy with Stand Up Virgin Soldiers, which jumps back in time and begins moments after The Virgin Soldiers ends, with Brigg learning that he has to return to Panglin for another six months – so (if I may be so bold) the threequel is a prequel to the sequel. Thomas realised that what people actually wanted from a Virgin Soldiers book was more of the same, and he gave it to them (complete with shamelessly resurrected Lucy), and a film version was quickly put into production.

The casting of Robin Askwith, toothily grinning icon of everything grubby, desperate and sad in low-budget British cinema of the 1970s, as Brigg, tells you all you need to know about the movie of Stand Up Virgin Soldiers. He and director Norman Cohen, then guiding Askwith through the pleasureless Confessions series of sex-comedies, were the Scorsese and De Niro of smutty crud. Stand Up was filmed between Confessions of a Driving Instructor and Confessions from a Holiday Camp, and much of it plays like ‘Confessions from Singapore’, including Miriam Margoyles as a Chinese whore called Elephant Ethel (offensive at every level), topless ‘native girls’ bathing in the river, deadening slapstick, staggeringly crude dialogue, and when the soldiers finally soldier very late in the film it’s a shameless, insincere attempt to simulate the tragic heft of the first film. Nigel Davenport as Driscoll is the only returnee, and he’s a decade older, heavier and wearier – poor bastard. Thomas’s influence (he has sole screenplay credit, he'd not write another film) is felt during the protracted romance between Brigg and a nurse, played with visible hesitation by Pamela Stephenson. The whole thing was shot in Elstree studios (home of the Confessions films), and although Thomas told The Straits Times that Singapore had changed too much by ‘76 to film there (a significant and not inaccurate observation), the production was just far too cheap (and disinterested in authenticity) to have ever seriously considered a location shoot. As a sidenote, the year that Stand Up was released, '77, also saw the stage premiere of Peter Nichols' Privates On Parade, a musical based on Nichols' time in an entertainment unit for the troops in Singapore and Malaya in the late 40s, with the Emergency as a backdrop. It was filmed in 1982, none of it in Singapore.

While The Virgin Soldiers was never masterpiece, it’s a fascinating adaptation of a deceptively powerful book, telling a story about a mostly forgotten war and a specific time in Singaporean and Malaysian history. The tawdriness of the sequel managed to tarnish the memory of the original. The VHS tape of the original film was ubiquitous in Smiths and Woolworths when I was growing up, and I just assumed (from the awful cover and the blurb on the back) that it was another bad sex comedy.

Meanwhile (back in the '60s), Singapore now had two big-budget Hollywood films under its belt and it looked as if the dream of it becoming a legitimate centre for high-profile American film production in East Asia was becoming reality. In September 1968 the press announced excitedly that six “big budget films” were aiming to film in Singapore over the next two years. MGM had two in pre-production, Fred Zinnemann's version of Man’s Fate, starring David Niven, and an adaptation of James Clavell's Tai Pan, starring Patrick McGoohan. In 1969, the year The Virgin Soldiers finally saw the light of day, both got very close to starting, Singaporeans were cast, including hundreds of extras, crew were employed and bills were racked up with local companies. The Zinnemann was a day away from its first day on set. Both were cancelled. The dream was over, as was the film industry in Singapore. The next notable foreign film shot in Singapore was Wit's End just before Christmas (and its director Joel Reed remembers the anger over Man's Fate), and then almost nothing until 1978 when Peter Bogdanovich showed up, and we know how that turned out.